This is Our Music is the militantly expressed jumping-off point for alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman on the way to the epochal Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation (Atlantic, 1961). Coleman picks up exactly where he left off on Change of the Century and never looks back. He keeps his working band mostly intact save for replacing drummer Billy Higgins with the like- wise sympathetic Ed Blackwell, who adds a phosphorous spark to the proceedings.

Coleman's recordings leading up to the defiant This is Our Music all bear prophetic, even apocalyptic titles: Something Else!!!! (Contemporary, 1958), Tomorrow is theQuestion!!!!(Contemporary, 1959), The Shape of Jazz to Come (Atlantic, 1959) and Change of the Century (Atlantic, 1959). Coleman's choice to title his next recording This is Our Music sounds like a response those critics less sympathetic to his approach in the late 1950s. Coleman takes a stand here, pushing his vision of musical freedom farther than on any previous release.

It is true enough that This is Our Music, opens with "Blues Connotation," a "relatively" straight-forward piece that echoes the opening of Change of the Century in the exquisite "Ramblin.'" Both pieces are steeped in Coleman's Texas blues tradition, brimming with angry virtuosity expressed via craggy skinned- knuckles. Coleman stands on his creative fulcrum, and looks both ways. On the previous Change of the Century the saxophonist carefully recaps his evolution over the previous recordings, ending his consideration with the fully untethered title cut, Coleman's statement that, as far as he was concerned, jazz will never be the same again. On the current recording, after the quasi-contained "Blues Connotation," Coleman fully leaps the edge of tradition into the chaotic and sublime future he, himself, was forging.

The remaining six compositions on This is Our Music firmly foreshadow the next recording, Free Jazz: A Group Improvisation. Melody, harmony, rhythm and time all become Salvador Dali-elastic, gleefully defying Einstein's space-time continuum. Even the only example of a "standard" in Coleman's free library, the Gershwin Brothers'"Embraceable You," is deconstructed and presented in its naked atomic elements. You can find the lost melody, but you must listen closely. And close listening reveals the other creative charms of Coleman's approach. "Embraceable You" is cast as a sound-clip from a noir mosaic, introspectively self- conscious, clothed casually in confidence. It is fitting, in some crazy appropriate way, that Coleman chose "Embraceable You" as his only standard to record during his Contemporary/Atlantic Days.

In October 1947, alto saxophonist Charlie Parkerrecorded "Embraceable You" with trumpeter Miles Davis, pianist Duke Jordan, bassist Tommy Potter and drummer Max Roachfor Ross Russell's Dial label. Parker immediately expressed a different melodic invention over the introductory chords of the well-worn piece, starting a new revolution in improvisation. Where Parker liberated the melody, Coleman set everything else free. Outside of the briefest directorial nudges, Coleman and company head in which ever direction inspired them individually.

"Beauty is a Rare Thing" is a free ballad that presents all of the instruments in their unattached roles. Coleman plays almost sweetly over Blackwell's rolling tom-tom figures. Bassist Charlie Hadenplays a moody arco, while Don Cherry squirts out tart pocket trumpet figures, once strung together, comprising a deranged yet unified solo. So with Cherry's duet sections with Coleman. The two provide one another a fractured counterpoint that resolves as often as it does not.

"Kaleidoscope" fully realizes Coleman's intentional lack of attention to melody and harmony with a frenetic and disjointed opening figure he plays in unison with Cherry and Blackwell. Each then solos like electricity skating across water, unhinged and seemingly without direction. Coleman shows that this is without peril by attaining a natural direction through the centrifugal force of the solo. Blackwell backs him in a way that drummer Elvin Jones would back saxophonist John Coltraneseveral years later, providing a dense rhythmic momentum.

This is Our Music is Coleman at the point of completely letting go. He and his most sympathetic supporters had evolved through varying musical perimeters to the point that he was prepared to forsake any limiting quantity or quality to his creation and performance. Coleman was introducing what Coltrane would perfect before the end of the 1960s, Coleman playing Vivaldi to Coltrane's Bach. - C. Michael Bailey

Coleman's recordings leading up to the defiant This is Our Music all bear prophetic, even apocalyptic titles: Something Else!!!! (Contemporary, 1958), Tomorrow is theQuestion!!!!(Contemporary, 1959), The Shape of Jazz to Come (Atlantic, 1959) and Change of the Century (Atlantic, 1959). Coleman's choice to title his next recording This is Our Music sounds like a response those critics less sympathetic to his approach in the late 1950s. Coleman takes a stand here, pushing his vision of musical freedom farther than on any previous release.

It is true enough that This is Our Music, opens with "Blues Connotation," a "relatively" straight-forward piece that echoes the opening of Change of the Century in the exquisite "Ramblin.'" Both pieces are steeped in Coleman's Texas blues tradition, brimming with angry virtuosity expressed via craggy skinned- knuckles. Coleman stands on his creative fulcrum, and looks both ways. On the previous Change of the Century the saxophonist carefully recaps his evolution over the previous recordings, ending his consideration with the fully untethered title cut, Coleman's statement that, as far as he was concerned, jazz will never be the same again. On the current recording, after the quasi-contained "Blues Connotation," Coleman fully leaps the edge of tradition into the chaotic and sublime future he, himself, was forging.

The remaining six compositions on This is Our Music firmly foreshadow the next recording, Free Jazz: A Group Improvisation. Melody, harmony, rhythm and time all become Salvador Dali-elastic, gleefully defying Einstein's space-time continuum. Even the only example of a "standard" in Coleman's free library, the Gershwin Brothers'"Embraceable You," is deconstructed and presented in its naked atomic elements. You can find the lost melody, but you must listen closely. And close listening reveals the other creative charms of Coleman's approach. "Embraceable You" is cast as a sound-clip from a noir mosaic, introspectively self- conscious, clothed casually in confidence. It is fitting, in some crazy appropriate way, that Coleman chose "Embraceable You" as his only standard to record during his Contemporary/Atlantic Days.

In October 1947, alto saxophonist Charlie Parkerrecorded "Embraceable You" with trumpeter Miles Davis, pianist Duke Jordan, bassist Tommy Potter and drummer Max Roachfor Ross Russell's Dial label. Parker immediately expressed a different melodic invention over the introductory chords of the well-worn piece, starting a new revolution in improvisation. Where Parker liberated the melody, Coleman set everything else free. Outside of the briefest directorial nudges, Coleman and company head in which ever direction inspired them individually.

"Beauty is a Rare Thing" is a free ballad that presents all of the instruments in their unattached roles. Coleman plays almost sweetly over Blackwell's rolling tom-tom figures. Bassist Charlie Hadenplays a moody arco, while Don Cherry squirts out tart pocket trumpet figures, once strung together, comprising a deranged yet unified solo. So with Cherry's duet sections with Coleman. The two provide one another a fractured counterpoint that resolves as often as it does not.

"Kaleidoscope" fully realizes Coleman's intentional lack of attention to melody and harmony with a frenetic and disjointed opening figure he plays in unison with Cherry and Blackwell. Each then solos like electricity skating across water, unhinged and seemingly without direction. Coleman shows that this is without peril by attaining a natural direction through the centrifugal force of the solo. Blackwell backs him in a way that drummer Elvin Jones would back saxophonist John Coltraneseveral years later, providing a dense rhythmic momentum.

This is Our Music is Coleman at the point of completely letting go. He and his most sympathetic supporters had evolved through varying musical perimeters to the point that he was prepared to forsake any limiting quantity or quality to his creation and performance. Coleman was introducing what Coltrane would perfect before the end of the 1960s, Coleman playing Vivaldi to Coltrane's Bach. - C. Michael Bailey

Tracks

1. Blue Connotation

2. Beauty Is A Rare Thing

3 Kaleidoscope

4. Embraceable You

5. Poise

6. Humpty Dumpty

7. Folk Tale

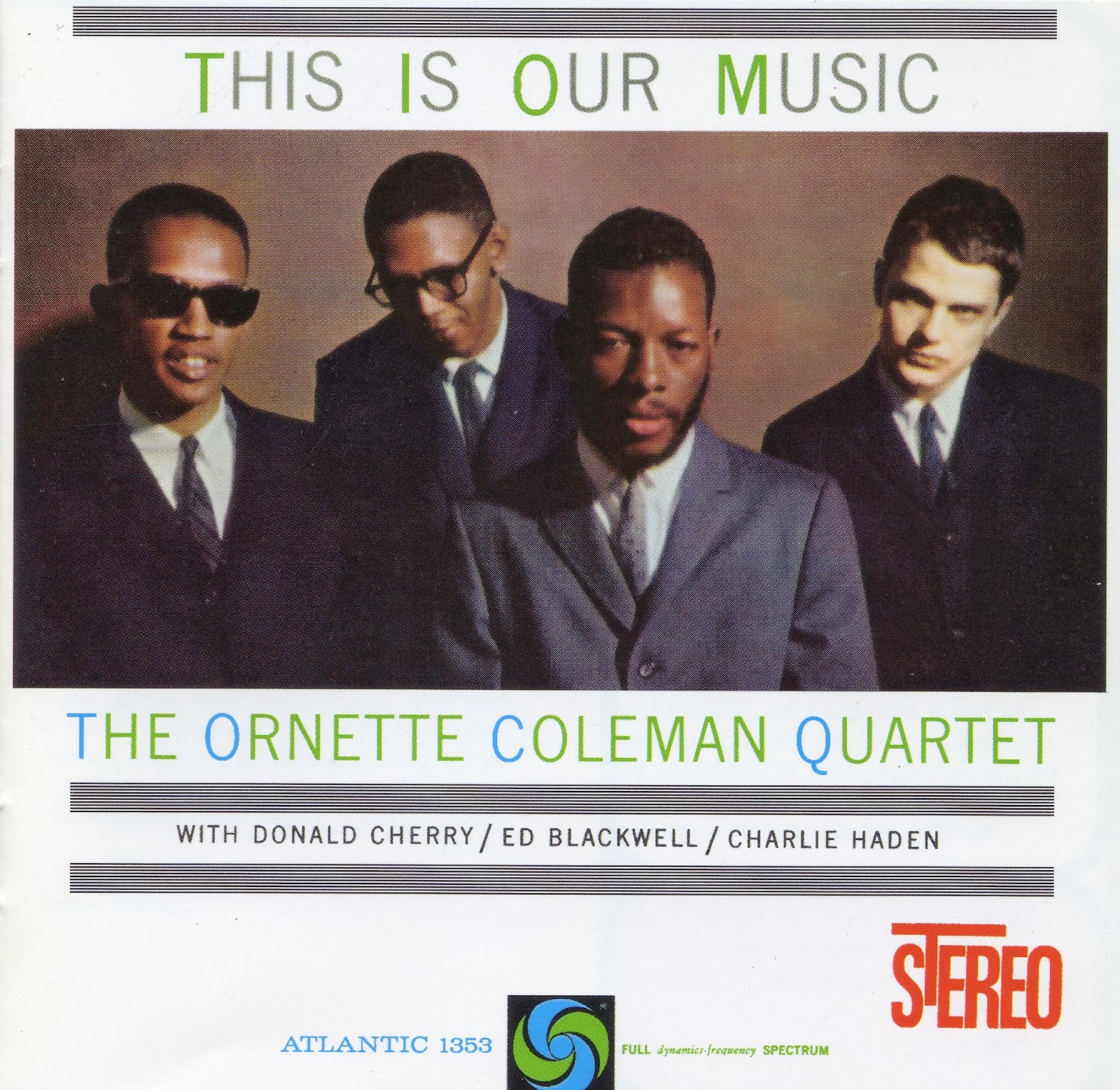

ORNETTE COLEMAN alto saxophone

DONALD CHERRY pocket trumpet

CHARLIE HADEN bass

ED BLACKWELL drums

All compositions by Ornette Coleman except "Embraceable You" by George and Ira Gershwin

Atlantic 1353 / 80767-2

1. Blue Connotation

2. Beauty Is A Rare Thing

3 Kaleidoscope

4. Embraceable You

5. Poise

6. Humpty Dumpty

7. Folk Tale

ORNETTE COLEMAN alto saxophone

DONALD CHERRY pocket trumpet

CHARLIE HADEN bass

ED BLACKWELL drums

All compositions by Ornette Coleman except "Embraceable You" by George and Ira Gershwin

Atlantic 1353 / 80767-2